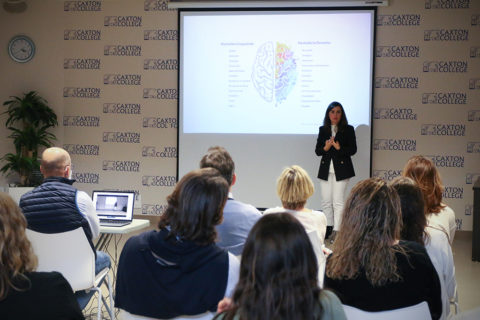

Dr Nuria Yáñez, child psychiatrist, gave a conference at Caxton College for its educational community about how to deal with the emotional and mental health issues caused by the pandemic.

The improved epidemiological situation in Spain and removal of the majority of restrictions is now allowing society to gradually return to normality. However, despite this optimistic situation, there are still many aftereffects of the pandemic on the population. On this subject, Dr Yáñez, coordinator of the Miguel Servet Mental Health Unit, described how children and adolescents have particularly suffered during this historic event and the impact it has had on them. ‘During lockdown, our patients—despite all expectations—managed very well. There was a decrease in consultations and emergencies. There were even patients who improved. We refer to that period of time as the “honeymoon period”’, said Dr Yáñez. But when the de-escalation period started, everything changed. Parents had to return to work and could no longer dedicate as much time to their children. ‘At that point, we did detect an increase in the number of children who came to consultations about behavioural issues’. As the psychiatrist said, ‘For children to go 177 days without going to school and seven months without stepping into a park was disastrous’.

But the return to school did not improve the statistics. ‘We encountered cases of anxiety, clinical depression and adolescents who were self-harming. There were problems with absences from school and serious behaviour problems in pupils with special educational needs (SEN) due to the difficulties they were having adapting to the school environment, which they found stressful after such a long absence’, she said.

Factors causing mental health issues

What are the factors that have altered the mental and emotional health of children and adolescents in the past two years? Some of the most significant ones, according to Dr Yáñez, were associated with the amount of time spent with technological devices, the lack of physical activity, the anxiety they experienced due to an excess of information and the stress levels at home due to deaths, hospitalisations, problems with work-life balance or decrease in family income.

Dr Yáñez added, ‘We have also found that some children who were born during the pandemic are experiencing difficulties in their verbal, motor and cognitive development, often in families with a lower socioeconomic level. We have also observed an increase in the number of children up to age seven who are suffering from anxiety, have fears about their safety, show egotistical behaviour patterns, demand more attention and become desperate when they don’t get what they want. In children between age seven and thirteen, we have detected symptoms of depression. And from age 13 to 18, we are seeing more cases of depression, anxiety and stress. In addition to these symptoms, we have even seen cases of self-harm and suicide attempts’.

On a positive note, the doctor stated that many of these problems improve or even disappear over time if children receive the right treatment.

Suggestions for improving behaviour

To manage this kind of behaviour, this specialist in child psychiatry had a series of recommendations for parents and teachers. ‘It’s essential that we teach children resilience so that they know how to overcome situations of adversity. It’s very good for them to maintain social relationships and practise extracurricular sport. Another aspect it’s important to bear in mind is that children should not have unlimited access to the news media; any information they receive should be filtered by an adult. It’s also very important for us to listen to them, validate their opinions and help them to express their emotions and ideas. For younger children, play is essential to healthy mental development since this is how they process all of their experiences’.

Whole brain

Dr Yáñez provided a clear but scientific explanation of how parents and educators can handle tantrums in children, given that these episodes have also increased as a result of the pandemic. ‘For a child’s tantrum to stop, it’s necessary for the child’s higher brain, or neocortex, to connect with the lower, or reptilian, brain’. It’s this lower brain where tantrums originate, because rational thought does not take place there. She said this is why ‘it’s important to end the tantrum by activating the neocortex, the higher part of the brain where reasoning takes place’. But how can this be achieved? Dr Yáñez explained: ‘It’s helpful to ask the child questions that will help them awaken their rational side, negotiate with them, ask them for alternatives or suggestions. This is how we can help the child release the irrational side and start to reason. At these times, body movement can help the two parts of the brain to connect, so it’s helpful for children to move around when they are overcome by anger. If they’re adolescents, you can ask them to walk or go up and down stairs, for example, because that’s when the two parts of the brain will connect and they can free themselves from that mental block’.