Stephen Anderson’s family history is almost as interesting as the food served in his restaurant near the Plaza de la Virgen, but not quite.

Picture this: Sir William Carr, a High Court Judge for the British Empire in Burma, strolls nonchalently through the colourful, spice-sodden market of Rangoon on a steamy, sultry monsoon morning, with his mind on his very special vice.

He hasn’t smoked a good cheroot in days and his body is aching for nicotine, named after Jean Nicot, French Ambassador to Lisbon, and the first European to cultivate tobacco.

Sir William spots a fine looking lassie rolling cheroots upon her lap and all at once two burning passions were about to catch fire.

Or something like that. Stephen isn’t absolutely sure, but what he does know is that Sir William was his great grandfather, and the union of those two characters in the market that day would lead to Valencia gaining a popular restaurant, offering Meditteranean cuisine with Asian touches, in a quiet pedestrian street just off the Plaza de la Virgen.

At about that time, the head of the Civil Service issued an order that British gentleman were to stop cavorting with native women, and a whole bunch of mistresses were suddenly dropped like hot curried potatoes; except for Sir William, who broke with years of colonial tradition and actually married the filly!

Sir William and his Burmese wife had many children, one of whom was Stephen’s grandmother. She broke with tradition by marrying a Burmese librarian and musician, who would later become Minister of Culture. They had three children, one of whom was Stephen’s mother.

“After the war Stephen’s Granny divorced her Burmese husband and married a Briton, Charles Barns, which is why, at the age of 14 Stephen’s mother found herself in Britain, where she eventually studied medicine, before marrying (as was the family tradition, sort of) a Welshman from Swansea.”

Although he spent most of his youth in Newport, South Wales, Stephen was born in Bethnal Green, East London, and his birth, ironically, was registered in a building that is now a restaurant. Somebody was obviously sending him a career message.

The message didn’t get through however, as he studied Physics at Bath University, and taught it for three years in South London.

However the call of the East was pulsing in his blood, and in 1991 he thought he’d try a year in Spain, which turned into two years teaching at a private academy and then at the American School.

Meanwhile, fate was once again taking a hand; his parents attended a cookery holiday in Umbria run by and for middle aged ladies. The lady who ran it was short on personal skills and so his parents suggested that Stephen spend his holidays there, helping out.

One of the cooks was Alistair Little, owner of a famous restaurant in London’s Soho. Suddenly the formula E=MC2 lost its appeal and the recipes of Soho called.

After a year learning the trade, Stephen returned to Valencia and opened SEU Xerea in 1996 in what had previously been an art gallery in C/ Conde de Almodóvar 4. Now a new kind of art is available, created with the culinary skills of Stephen, who moves between kitchen and restaurant, innovating, depending on what he has seen on his visits to Thailand, Malasia and Vietnam, and what was available that day at the fish auction in the port, in the Central Market, and in his own fields in Alboraya where he grows his own vegetables, including eastern ingredients such as lemon grass. His meat comes from a butcher in the village of Viver.

If he runs out of ideas for how to make the most of an asparagus or monkfish, he can always ring his friend and business partner Bernd Knöller, owner of the Michelin star restaurant Riff for ideas.

As well as sharing a passion for cooking, they have also invested in a gourmet shop next to Riff in Calle Conde de Altea, mostly run by fellow Briton Dan Gill.

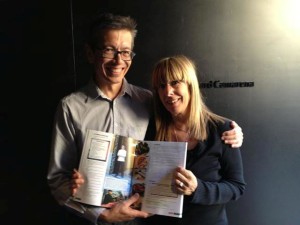

Stephen is a well known figure among the foreign population of Valencia, although you’ll find neither baked beans nor fish and chips on the menu. So well known is he in fact that an interview with him features in a recently published English language textbook, English File Intermediate, written by Valencian based writers Clive Oxenden and Christina Latham Koenig.

Stephen is a well known figure among the foreign population of Valencia, although you’ll find neither baked beans nor fish and chips on the menu. So well known is he in fact that an interview with him features in a recently published English language textbook, English File Intermediate, written by Valencian based writers Clive Oxenden and Christina Latham Koenig.

I’d already eaten there about three times before interviewing Stephen. The first time I was there we were offered an aperitif of crunchy crayfish in ‘ceps’ sauce (I had to look it up too, but it’s a kind of wild mushroom), followed by thinly sliced cod Carpaccio with ‘escalibada’, a Catalonia purée made of vegetables, and then Italian Polenta with mini squids.

The menu stretched my linguistic ability, but each dish, with its immaculate cutlery and crockery was a joy to eat. The accompanying wine was excellent too, and I must confess I didn’t study the list as obsessively as I usually do, having spotted straight off a fruity Basque wine of the ‘Txakoli’ variety, which you don’t often see in many places outside of the Basque Country.

For the main course we had three choices; salmon with black tagliatelle and sweet and sour sauce, pork sirloin stuffed with nuts and pumpkin sauce, or an octopus risotto.

Finally the dessert was a cheese mousse with poppy seeds and cassis ice cream.

The service was excellent and the waitresses, in their tight black uniforms, would have turned a younger, more foolish man’s head to thoughts of Burmese days.

Another time there was chicken breast in green curry and salmorejo (similar to Gazpacho).

Local raw materials with a touch of eastern exoticism and a rampant cavalcade of spice and herbs that always complement and never send you running for the fire hose. Stephen himself sums up the Seu Xerea experience, calling it globally local food.

I also spent my 25th wedding anniversary there with my wife, who had forgotten this trivially insignificant occasion as usual and consequently offered to pay with my credit card.