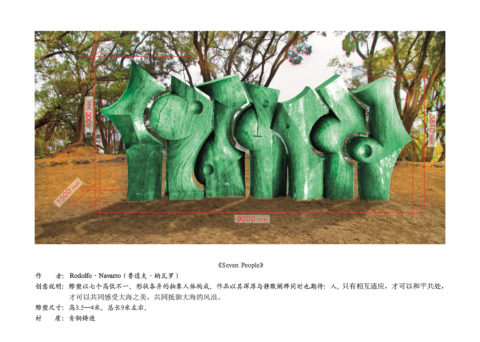

The latest news about Valencian artist Rodolfo Navarro is that he has been contracted by China’s third largest city, Shenzen, to erect a statue in one of its squares.

The statue is entitled Seven People and should be installed before the end of 2016.

4 metres high, and consisting of 7,000 kilos of bronze, the seven people in the figure will be seen by the city’s 15,000,000 inhabitants.

In 2014 we write this about Navarro:

How many artists have exhibited on The Great Wall of China? Let me save you time calculating and say that there has only been one: Valencian artist Rodolfo Navarro.

Rodolfo Navarro is not a typical artist, one content to see his work exhibited in an ornate frame inside an unvisited museum or gallery. Rodolfo Navarro thinks big! For him an adequate framework for his art is the emblematic staircase of Fontainebleau Palace or the Great Wall of China.

Not that Rodolfo is a graffiti artist, his works were painstakingly prepared years before being hung on the wall; three years in fact, making Mao’s long trek pall into insignificance.

His career as an artist was undoubtedly influenced by two factors; the jewellery shop run by his father and set up by his great grandfather in the centre of Valencia, and the meeting at the age of 14 with the Valencian artist Rafael Pérez Contel.

Like his father, Rodolfo would eventually qualify as a gemmologist from the Gemmological Association of Great Britain, the first of its kind in the world; but although he still includes some jewels in his sculptures, it is his large scale, complex paintings designed to fit into specific open places that has made his name well-known in artistic circles.

Contel was a frequent visitor to the jewellery shop, where he would bake his figures in the Navarro ovens, but chose the losing side in the Civil War, being jailed for three years, and having to disguise hammer and sickle symbols on his figurines where only sympathisers would notice them.

This was the beginning of a mentor and disciple relationship that would last until Contel’s death in 1991, with young Rodolfo learning the trade at his master’s side and developing his own knowledge and style.

Later Rodolfo would begin along the traditional path of studying at the School of Fine Arts, but as one of the first Spaniards to obtain an Erasmus grant, only two years after Spain’s adhesion to the European Union, he took off for Paris in 1988 with a year’s scholarship that would turn into seven years of study and work and marriage to a French Art History student at the Sorbonne, Marie-Noëlle, with whom he has since had four delightful daughters.

Life in Paris was a classic Bohemian experience; lack of heating and money not distracting him from his artistic ambitions as he learnt the trade, visiting all the museums and producing hundreds of sketches of all the classical sculptures.

As he told me in his sprawling home and studio in the open countryside near Llíria, Art is something you have to work at, “even more complex than learning a musical instrument to a high level”.

During his time in Paris he became fascinated by shadows and light, especially in the massive interior of Notre Dame Cathedral. He was also at the beginning of the 90s developing the idea of art within a context, and of developing paintings that were large enough to be seen from a distance, and that used natural or urban surroundings as the painting’s frame.

He therefore worked on a painting measuring seven by seven metres that he would take to different parts of Paris to be displayed, in the Palais des Etudes (E.N.S.BA). and later displayed under the Eiffel Tower and in front of the Georges Pompidou centre.

In 1996 he produced a seminal work when he used the emblematic ‘horseshoe’ staircase at Fontainebleau Palace as the framework, with a 250 square metre painting called: ‘Carré Rouge, Triangle Jaune, Cercle Bleu’ somehow managing to convince the authorities there with his characteristic smile that the various pieces that made up the ensemble were art rather than litter.

Although the various parts were for sale, he also foresaw the advantage of exploring his love of photography in order to set up touring exhibitions showing photos of the work along with any unsold parts.

In 1997 he repeated his idea with another exhibition, this time in the courtyard at the Wolfsburg Museum in Germany, near Berlin, with a 350 square metre picture called: ‘the transfiguration’.

As is so often the case for Valencian people, the call of the homeland is loud and by 2002 he was back home draping his work over the floor of the cloister of the Faculty of Theology near the Serranos Towers with a 400 square metre picture called: ‘Cuadrocubo’.

A clear style had by this time emerged of anatomical figures, incomplete figures or figures that blended with their background, vivid colours and sculptures strategically placed.

His own personal Long March began in 2004 when he met a Chinese architect who put him in touch with Zhang Ling, President of Capital Media Corporation, who organize the Beijing Music Festival, and a man who he now describes as being “like a brother”. The idea of tackling the Great Wall began to blossom, and the journey that he describes with hindsight as a “enormous, mad adventure” and that Zhang Ling described inscrutably at its inception as “not impossible”, would lead to a three day exhibition in October 2008 of a 1,000 square metre work plus 12 monumental sculptures, and involve eight separate trips to China, the last of which, prior to the exhibition, would last three months and include the whole family.

Despite some financial help from the Valencian government, other promised monies evaporated as deadlines approached and Rodolfo began to discover that the Chinese work ethic consisted largely of unimaginative obedience of the boss, if he was present. If he wasn’t, nothing was done.

Before he could begin, he had to convince the Chinese authorities of what he wanted to do. This involved designing a great part of the project, creating a Photoshop montage to show what it would look like, after having selected an appropriate spot and taken extensive measurements.

By June 2006 he received a call to say that they had, not exactly permission, but the ‘first permission’, and an agreement with Capital Media Corporation that would agree to organise it; if he was successful in working through the labyrinth of Chinese bureaucracy, which was of course on full throttle on its relentless path towards the 2008 Olympic Games.

At first the work was planned to be inaugurated in July 2007, and Rodolfo set to work furiously painting in Llíria in january 2006,long before obtaining permission, and later in rented warehouse space in China.

Eventually the date would be set back another year as Rodolfo battled with Chinese ‘Kleenex’ philosophy (that all things are to be used briefly and then replaced) and that all measurements should be taken by eye rather than using instruments, expressing his frustration in a mixture of English and Chinese, often with an interpreter at the end of a telephone.

In December 2007 he started the monumental sculpture, having left precise instructions on the work to be carried out meanwhile, only to discover that nothing whatsoever had changed in March 2008.

When July arrived he became a collateral victim of the protests against Chinese intervention in Tibet, because of which the Chinese government cancelled all cultural activities. The government’s ban on the transportation of ‘dangerous’ materials also meant that he was unable to obtain resin for the final stages of his sculptures. Then with a few days remaining before the opening, with the crucial last touches to be added, he discovered that early October was when the Chinese celebrate their national holiday, and of course, nobody worked.

Meanwhile the children should have started school and so they were receiving classes from Marie Noëlle from the torn out first few pages of their course books brought across from Spain, and two hours of classes with a Chinese teacher in the afternoons.

Lapses in the work however did permit them to undertake a fascinating journey into the Chinese heartland, where few Westerners ever go, and to visit, among other things, Mao’s house.

Finally the inauguration day came……… and went. High winds made it impossible to hang the paintings, and it wasn’t until a few days later that the exhibition finally took place, inaugurated by the Valencian government Culture Secretary Rafael Miró, in the presence of various Chinese cultural and political figures.

Nevertheless, nothing is over until it is truly over and Valencia was able to get a glimpse of what the experience was like with an exhibition held at the Atarazanas exhibition centre near Valencia’s port at the end of 2011, as well as a display of Rodolfo’s sculptures along the Gran Via Avenue in central Valencia.

And yet, despite his great success all over the world, Rodolfo hasn’t forgotten his humble beginnings, or the efforts of his mentor to help him find his own talent and learn artistic techniques; and for this reason he opens his home to students of all ages, providing they have the patience and the willingness to learn.

According to him, “technique is not very important” and can be learnt in six months; the rest is a question of finding your own path, or long march.

I suddenly realised that two and a half hours had shot by, and yet Rodolfo didn’t seem inclined to throw us out; instead he posed with his father by the statue in his garden given to him by Rafael Perez Contel, reminiscent of the famous Robert Capa photograph of a Civil war soldier being shot, and showed me some of his library books by and about Contel.

As we left I scanned his work table, a landscape of the artist’s mind, containing among other things a skull, an electric drill, window cleaning liquid, paints, sculptures, photos, art books, a Tupperware, moulds and a paint roller; mere physical tools that somehow find a precise function in the unlimited creative spaces of the artist’s mind (although the Tupperware might have contained his lunch).